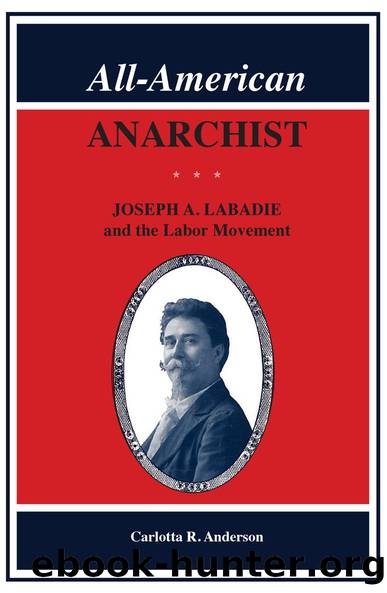

All-American Anarchist by Carlotta R. Anderson

Author:Carlotta R. Anderson [Anderson, Carlotta R.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Social Science, Regional Studies, Political Science, Labor & Industrial Relations, Biography & Autobiography, Social Activists

ISBN: 9780814343272

Google: v6U7DwAAQBAJ

Publisher: Wayne State University Press

Published: 2017-12-01T05:23:27+00:00

13

Pet Radical

In the regal realm of Me

I am rightful sovereign there;

None should question my decree,

None my wishes justly dare.

ââTHE TRUE SOVEREIGN,â WORKSHOP RIMES

Labadie always believed that if people could only see how thoroughly home-grown his kind of anarchism was, their terrors would be allayed. He thought if he could show that it sprouted from native soil and that its seed was the American love of liberty, he could persuade others to tolerate or even welcome it. Sometimes, to make the doctrine more palatable, he called it âphilosophicalâ anarchism (to his mind, as silly as saying âphilosophical philosophyâ) just so the word would not âstrike the puny mind with so much force as to knock it out in the first round.â1 Labadie could, of course, have called his philosophy âlibertarianism,â as many did (and do) and avoided the commotion. Perhaps he saw that as being dishonest, or perhaps he enjoyed the commotion.

Partly because its best-known anarchist was considered to be peace-loving and law-abiding, Detroit had escaped much of the frenzy that convulsed other cities after the Haymarket bombing. The influence of the large and well-respected German socialist community probably also played a role. Detroitâs radicals generally were tolerated as well-meaning reformers or impractical dreamers, no threat to the good burghers. But the affection Labadie enjoyed personally did not lessen his distress at the popular view of anarchists as âan ignorant, vicious, whisky-drinking gang, dirty in personal habits, careless of the rights of others, and ever ready to kill and burn,â the portrayal Powderly hysterically painted at the 1887 Minneapolis convention.2

Labadie felt driven to tell the nation about its anarchistsâwho they were, what they looked like, what they thought and why. For most of his life, he operated on a naive faith that once people were presented with the logic of a case, their innate rationality would lead them to fair-minded conclusions. If interested persons could be shown that anarchists were well-behaved, honest, and just, âa good deal like other folks,â they would be likely to examine the philosophy without prejudice.3

He first proposed that a conference of anarchists be held in Detroit in the summer of 1888, where they would issue to the world a clarifying âanarchistic manifesto.â Anarchists of all stripes could become acquainted and possibly reach harmony between the individualist and the collectivist branches. He expected it to be well covered by the press and attract widespread attention. His anarchist mentor Tucker scoffed at the idea as an excuse for an expensive junket with no clear purpose. He thought Labadie âsurprisingly ignorant of the nature of the beast known as a capitalistic newspaperâ if he thought a declaration of principles would stop malicious reporting.4

Rebuffed by American anarchismâs guru, Labadie shifted his attention to a book. No outline of the views of Americaâs anarchists had ever been published. In late 1888 and early 1889, he sent out forty or fifty letters to leading anarchists, asking them to define the philosophy, why it was desirable, and how it should be attained. They were to include a biographical sketch and picture.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19092)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12191)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8912)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6889)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6281)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5802)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5756)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5509)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5448)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5219)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5154)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5088)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4964)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4927)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4790)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4753)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4720)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4514)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4490)